A model is a representation of something else.

A class diagram is a model that represents a software design.

A model provides a simpler view of a complex entity because a model captures only a selected aspect. This omission of some aspects implies models are abstractions.

A class diagram captures the structure of the software design but not the behavior.

Multiple models of the same entity may be needed to capture it fully.

In addition to a class diagram (or even multiple class diagrams), a number of other diagrams may be needed to capture various interesting aspects of the software.

In software development, models are useful in several ways:

a) To analyze a complex entity related to software development.

Some examples of using models for analysis:

- Models of the can be built to aid the understanding of the problem to be solved.

- When planning a software solution, models can be created to figure out how the solution is to be built. An architecture diagram is such a model.

b) To communicate information among stakeholders. Models can be used as a visual aid in discussions and documentation.

Some examples of using models to communicate:

- You can use an architecture diagram to explain the high-level design of the software to developers.

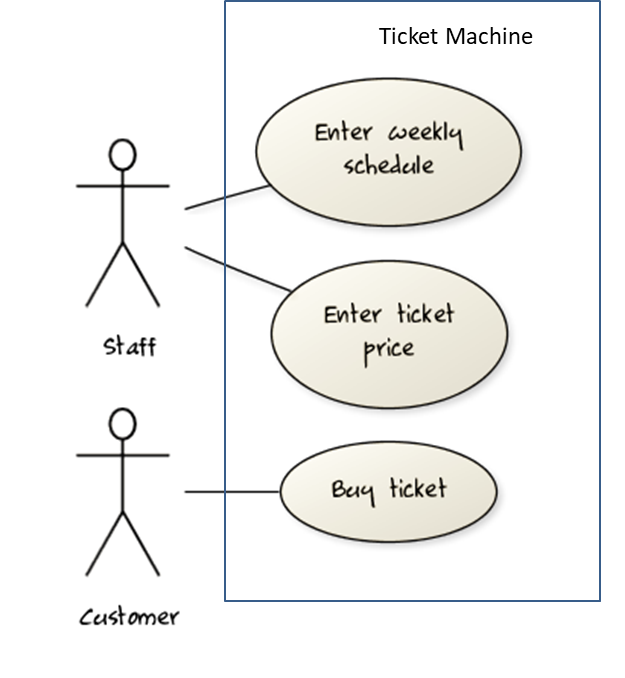

- A business analyst can use a use case diagram to explain to the customer the functionality of the system.

- A class diagram can be reverse-engineered from code so as to help explain the design of a component to a new developer.

c) As a blueprint for creating software. Models can be used as instructions for building software.

Some examples of using models as blueprints:

- A senior developer draws a class diagram to propose a design for an OOP software and passes it to a junior programmer to implement.

- A software tool allows users to draw UML models using its interface and the tool automatically generates the code based on the model.

Unified Modeling Language (UML) is a graphical notation to describe various aspects of a software system. UML is the brainchild of three software modeling specialists James Rumbaugh, Grady Booch and Ivar Jacobson (also known as the Three Amigos). Each of them had developed their own notation for modeling software systems before joining forces to create a unified modeling language (hence, the term ‘Unified’ in UML). UML is currently the most commonly used modeling notation used in the software industry.

The following diagram uses the class diagram notation to show the different types of UML diagrams.

source:https://en.wikipedia.org/

An OO solution is basically a network of objects interacting with each other. Therefore, it is useful to be able to model how the relevant objects are 'networked' together inside a software i.e. how the objects are connected together.

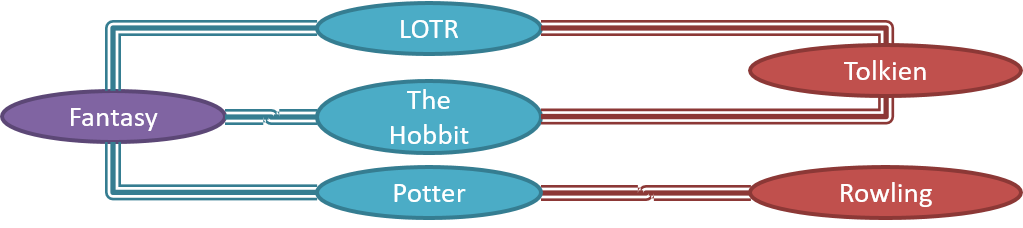

Given below is an illustration of some objects and how they are connected together. Note: the diagram uses an ad-hoc notation.

Note that these object structures within the same software can change over time.

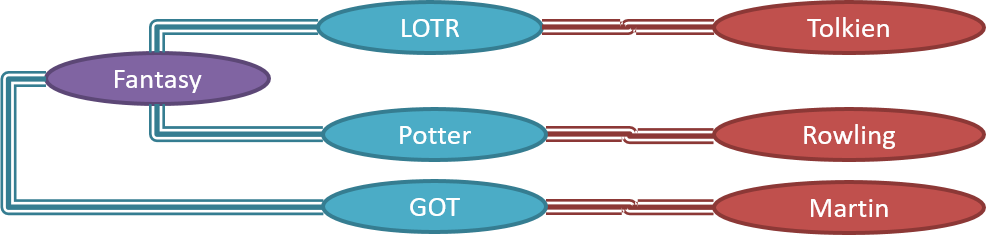

Given below is how the object structure in the previous example could have looked like at a different time.

However, object structures do not change at random; they change based on a set of rules set by the designer of that software. Those rules that object structures need to follow can be illustrated as a class structure i.e. a structure that exists among the relevant classes.

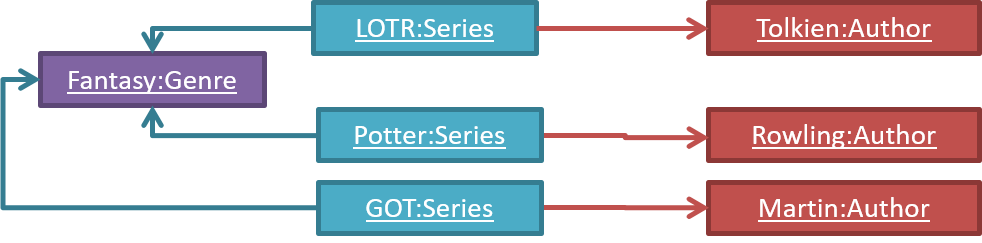

Here is a class structure (drawn using an ad-hoc notation) that matches the object structures given in the previous two examples. For example, note how this class structure does not allow any connection between Genre objects and Author objects, a rule followed by the two object structures above.

UML Object Diagrams model object structures. UML Class Diagrams model class structures.

Here is an object diagram for the above example:

And here is the class diagram for it:

Contents related to UML diagrams in the panels given below belong to a different chapter (i.e., the chapter dedicated to UML); they have been embedded here for convenience.

Classes form the basis of class diagrams.

UML Class Diagrams → Introduction → What

UML Class Diagrams → Classes → What

UML Class Diagrams → Class-Level Members → What

Associations are the main connections among the classes in a class diagram.

OOP Associations → What

UML Class Diagrams → Associations → What

UML Class Diagrams → Associations as Attributes

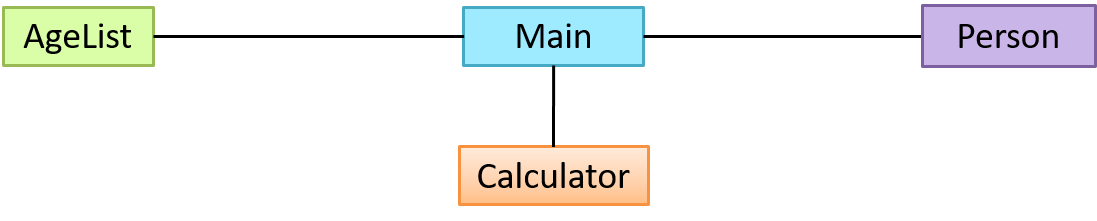

The most basic class diagram is a bunch of classes with some solid lines among them to represent associations, such as this one.

An example class diagram showing associations between classes.

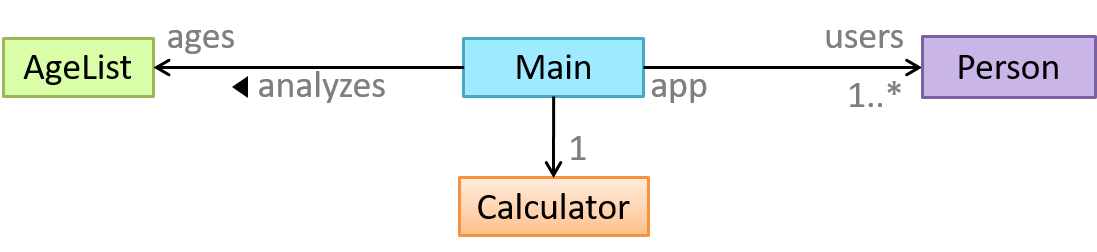

In addition, associations can show additional decorations such as association labels, association roles, multiplicity and navigability to add more information to a class diagram.

UML Class Diagrams → Associations → Labels

UML Class Diagrams → Associations → Roles

OOP Associations → Navigability

UML Class Diagrams → Associations → Navigability

OOP Associations → Multiplicity

UML Class Diagrams → Associations → Multiplicity

Here is the same class diagram shown earlier but with some additional information included:

A class diagram can also show different types of relationships between classes: inheritance, compositions, aggregations, dependencies.

Modeling inheritance

OOP → Inheritance → What

UML → Class Diagrams → Inheritance → What

Modeling composition

OOP → Associations → Composition

UML → Class Diagrams → Composition → What

Modeling aggregation

OOP → Associations → Aggregation

UML → Class Diagrams → Aggregation → What

Modeling dependencies

OOP → Associations → Dependencies

UML → Class Diagrams → Dependencies → What

A class diagram can also show different types of class-like entities:

Modeling enumerations

OOP → Classes → Enumerations

UML → Class Diagrams → Enumerations → What

Modeling abstract classes

OOP → Inheritance → Abstract Classes

UML → Class Diagrams → Abstract Classes → What

Modeling interfaces

OOP → Inheritance → Interfaces

UML → Class Diagrams → Interfaces → What

UML → Object Diagrams → Introduction

Object diagrams can be used to complement class diagrams. For example, you can use object diagrams to model different object structures that can result from a design represented by a given class diagram.

UML → Object Diagrams → Objects

UML → Object Diagrams → Associations

The analysis process for identifying objects and object classes is recognized as one of the most difficult areas of object-oriented development. --Ian Sommerville, in the book Software Engineering

Class diagrams can also be used to model objects in the (i.e. to model how objects actually interact in the real world, before emulating them in the solution). Class diagrams that are used to model the problem domain are called conceptual class diagrams or OO domain models (OODMs).

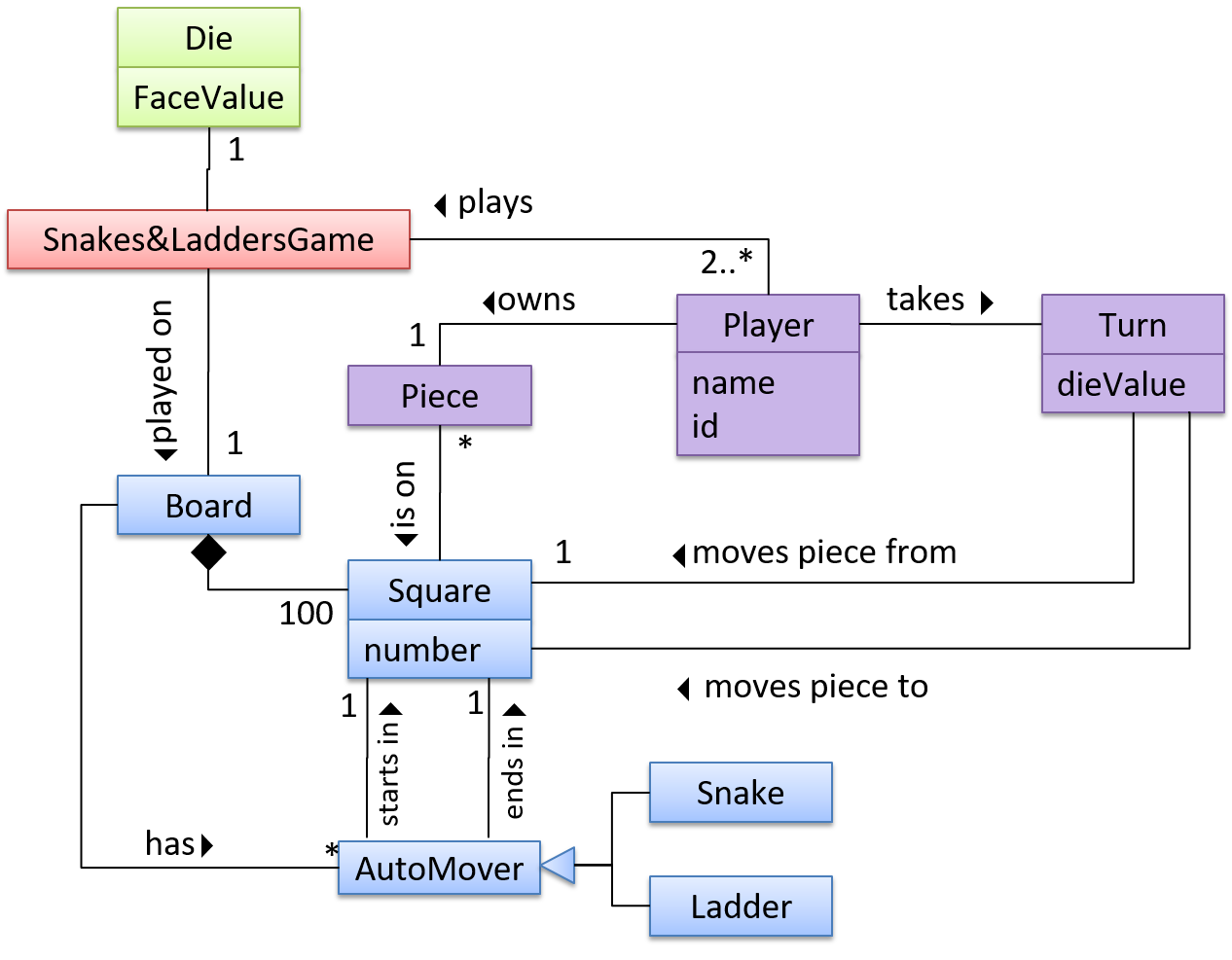

The OO domain model of a snakes and ladders game is given below.

Description: The snakes and ladders game is played by two or more players using a board and a die. The board has 100 squares marked 1 to 100. Each player owns one piece. Players take turns to throw the die and advance their piece by the number of squares they earned from the die throw. The board has a number of snakes. If a player’s piece lands on a square with a snake head, the piece is automatically moved to the square containing the snake’s tail. Similarly, a piece can automatically move from a ladder foot to the ladder top. The player whose piece is the first to reach the 100th square wins.

OODMs do not contain solution-specific classes (i.e. classes that are used in the solution domain but do not exist in the problem domain). For example, a class called DatabaseConnection could appear in a class diagram but not usually in an OO domain model because DatabaseConnection is something related to a software solution but not an entity in the problem domain.

OODMs represents the class structure of the problem domain and not their behavior, just like class diagrams. To show behavior, use other diagrams such as sequence diagrams.

OODM notation is similar to class diagram notation but omit methods and navigability.

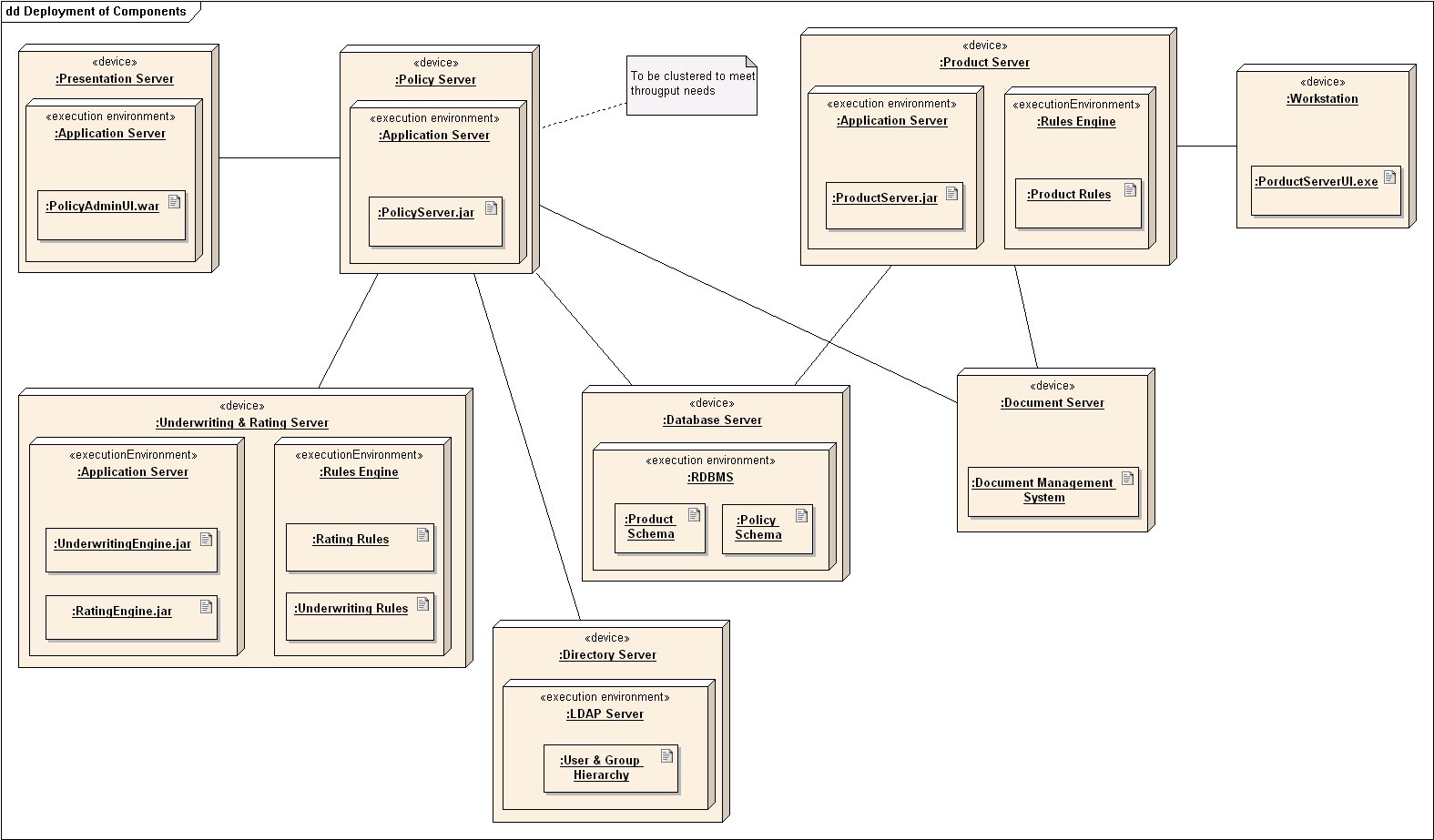

A deployment diagram shows a system's physical layout, revealing which pieces of software run on which pieces of hardware.

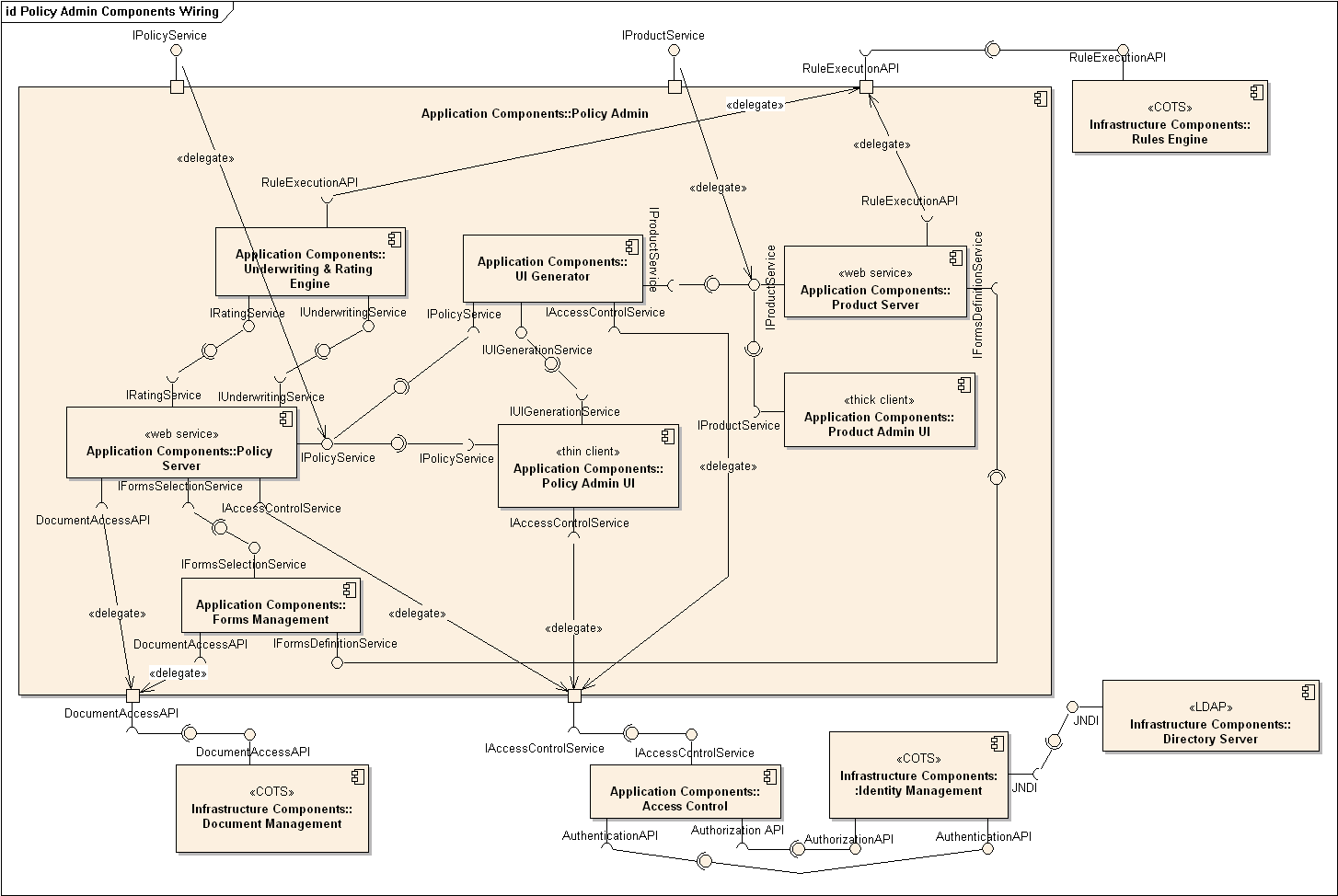

A component diagram is used to show how a system is divided into components and how they are connected to each other through interfaces.

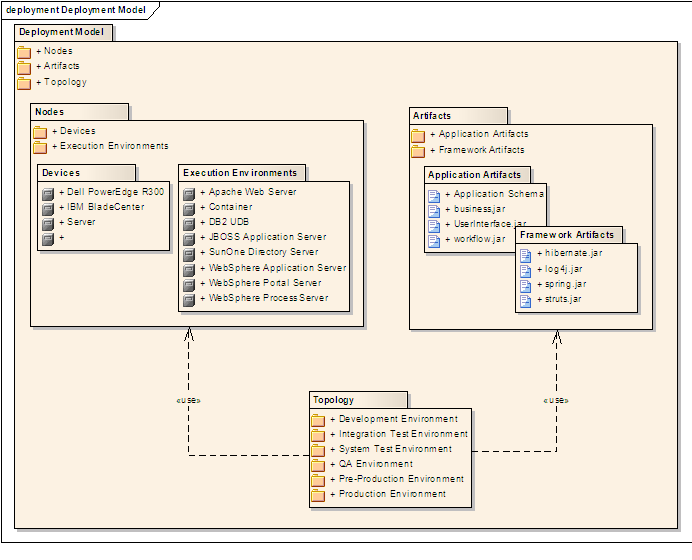

A package diagram shows packages and their dependencies. A package is a grouping construct for grouping UML elements (classes, use cases, etc.).

Here is an example package diagram:

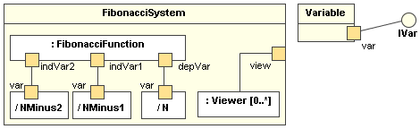

A composite structure diagram hierarchically decomposes a class into its internal structure.

Software projects often involve workflows. Workflows define the flow in which a process or a set of tasks is executed. Understanding such workflows is important for the success of the software project.

Some examples in which a certain workflow is relevant to software project:

A software that automates the work of an insurance company needs to take into account the workflow of processing an insurance claim.

The algorithm of a piece of code represents the workflow (i.e. the execution flow) of the code.

UML Activity Diagrams → Introduction → What

UML Activity Diagrams → Basic Notation → Linear Paths

UML Activity Diagrams → Basic Notation → Alternate Paths

UML Activity Diagrams → Basic Notation → Parallel Paths

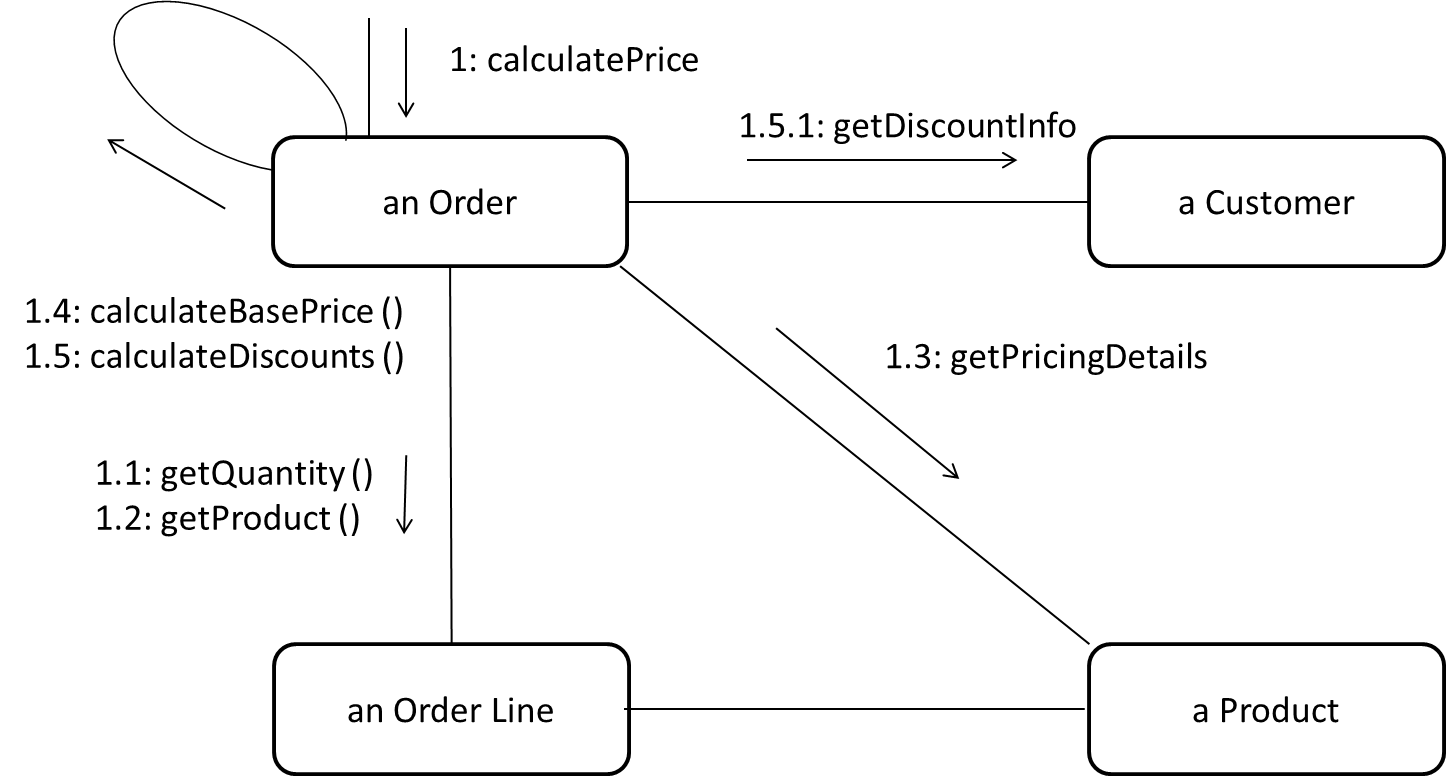

Sequence diagrams model the interactions between various entities in a system, in a specific scenario. Modelling such scenarios is useful, for example, to verify the design of the internal interactions is able to provide the expected outcomes.

Some examples where a sequence diagram can be used:

To model how components of a system interact with each other to respond to a user action.

To model how objects inside a component interact with each other to respond to a method call it received from another component.

UML Sequence Diagrams → Introduction

UML Sequence Diagrams → Basic Notation

UML Sequence Diagrams → Loops

UML Sequence Diagrams → Object Creation

UML Sequence Diagrams → Minimal Notation

UML Sequence Diagrams → Object Deletion

UML Sequence Diagrams → Self-Invocation

UML Sequence Diagrams → Alternative Paths

UML Sequence Diagrams → Optional Paths

UML Sequence Diagrams → Calls to Static Methods

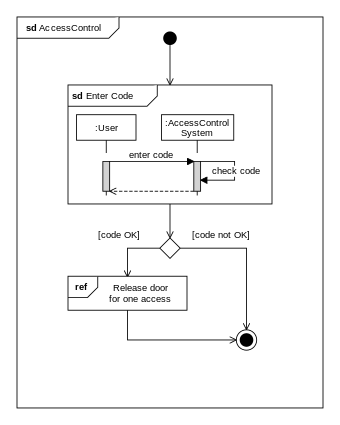

Interaction overview diagrams are a combination of activity diagrams and sequence diagrams.

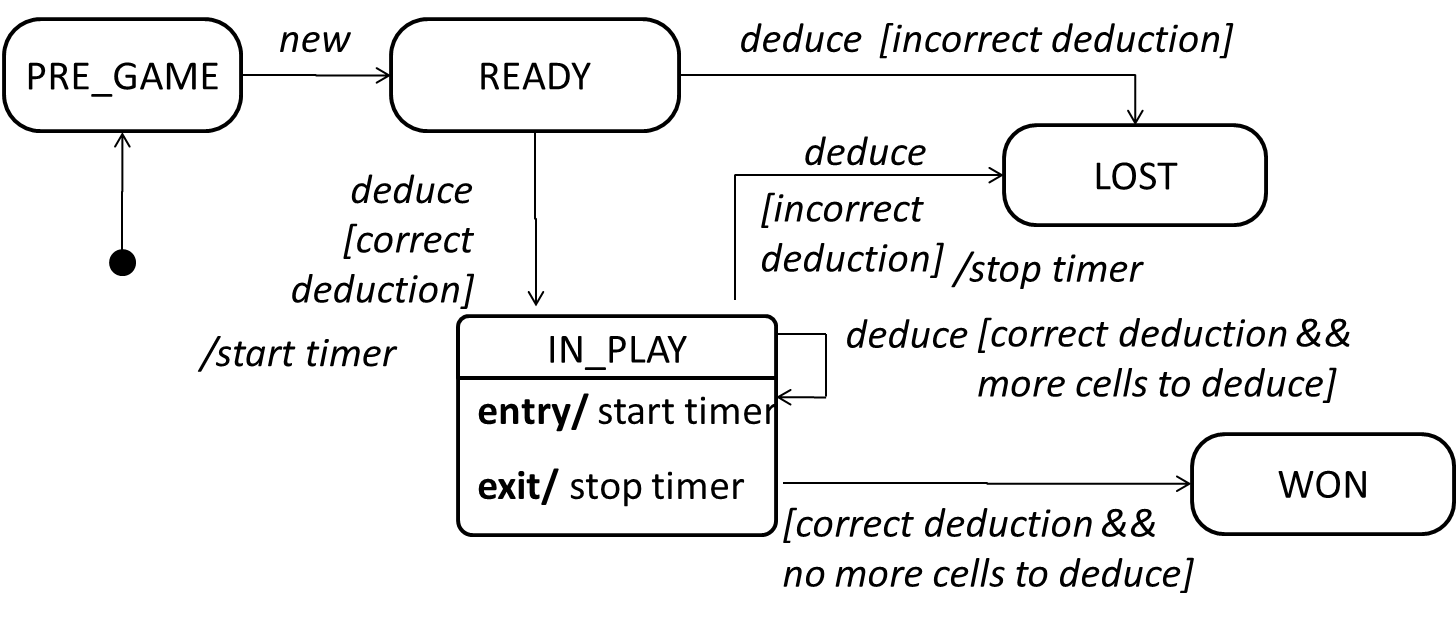

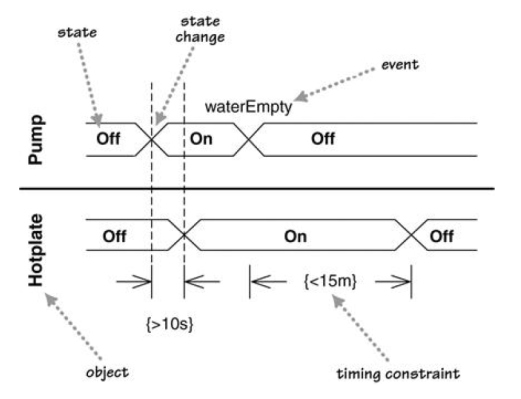

A State Machine Diagram models state-dependent behavior.

Consider how a CD player responds when the “eject CD” button is pushed:

- If the CD tray is already open, it does nothing.

- If the CD tray is already in the process of opening (opened half-way), it continues to open the CD tray.

- If the CD tray is closed and the CD is being played, it stops playing and opens the CD tray.

- If the CD tray is closed and CD is not being played, it simply opens the CD tray.

- If the CD tray is already in the process of closing (closed half-way), it waits until the CD tray is fully closed and opens it immediately afterwards.

What this means is that the CD player’s response to pushing the “eject CD” button depends on what it was doing at the time of the event. More generally, the CD player’s response to the event received depends on its internal state. Such a behavior is called a state-dependent behavior.

Often, state-dependent behavior displayed by an object in a system is simple enough that it needs no extra attention; such a behavior can be as simple as a conditional behavior like if x > y, then x = x - y.

Occasionally, objects may exhibit state-dependent behavior that is complex enough such that it needs to be captured in a separate model. Such state-dependent behavior can be modeled using UML state machine diagrams (SMD for short, sometimes also called ‘state charts’, ‘state diagrams’ or ‘state machines’).

An SMD views the life-cycle of an object as consisting of a finite number of states where each state displays a unique behavior pattern. SMDs capture information such as the states an object can be in during its lifetime, how the object responds to various events while in each state, and how the object transits from one state to another. In contrast to sequence diagrams that capture object behavior one scenario at a time, SMDs capture the object’s behavior over its full life-cycle.

An SMD for the Minesweeper game.